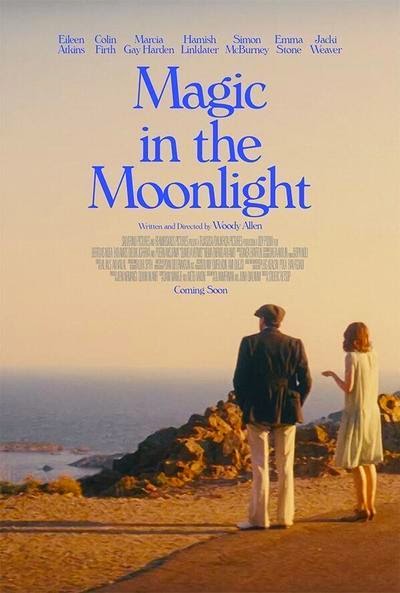

Magic in the Moonlight - a review and a slight digression on love

To

enjoy a Woody Allen film after an honest day’s work is a fine way to whittle away an

evening. From the familiar font of the opening credits to the first cords of

Cole Porter, the unmistakeable stamp of the little genius suffused through the

cinema.

Magic

in the Moonlight bears all the hallmarks of Allen films of late: beautiful

scenery (set in Provence in the golden 20’s) bathed in golden light, attractive

characters with distinct personalities, witty conversation and existentialist quarrels.

The

story unfolds around Stanley (Colin Firth), a misanthropic, egotistical, cynical,

sarcastic and world famous magician. He is beseeched by a friend to unmask

Sophie Baker (Emma Stone), an American clairvoyant who has established herself

with a gullible and wealthy family.

Essentially, the film is a story of an emotionally arid middle-aged man whose passions are unwittingly

and grudgingly rejuvenated by the wellspring of beauty, youth and mystique of

the wondrous. In other words, it is the battle between cynicism and romanticism,

with both factions starting from their respective extreme ends and meeting

somewhere in the middle. Hence, it can be seen as a metaphorically

autobiographical film for the director – the aging artist reinvigorated by

youth (Allen’s own rather sordid household arrangement with his former adopted

daughter may be a bit of a stretch even for an eccentric artiste) and the two

sides of his nature, the incurable romantic versus the ironic, wry, atheist Jewish

comic.

Colin

Firth was curiously flat in the first third but picks up marvelously. It takes

great subtlety and comic timing to portray well the adorable disorder of dignity

gone awry. His slightly cheesy, slightly self-conscious and slightly self-deprecating

grin and eyes imbued with sensibility takes the edge off of Stanley’s crusty

and caustic personality and makes him appear vulnerable, which is an essential characteristic in a

comic role. Especially pertinent was this when he talks to his aunt, his proxy mother, played in a

delightful minor key by Eileen Atkins.

The

doe-eyed Emma Stone was fantastically cast. There is a refreshing lack of

pretension in her acting, something rare in the new wave of young actors. Her charms, helped by her alarmingly large and limpid eyes, come across with a innocence and openness that counterbalances her role as the mountebank. Her

slightly exaggerated moments whilst ‘under’ is a joke both at the expense of

the spiritualists and a breaching of the forth wall and a wink to the audience. Whilst

sharing great chemistry, the two emanated not so much eros but agape. They would have

made a great father and daughter. An element of reverse Pygmalion also abounds,

where instead of the man of the world making a lady out of the Cockney flower

girl, it is the American charlatan who rekindles the fire of passion in the

middle-aged artist.

The

central message seems to be that despite the disingenuousness and ultimate disappointment

of spiritualism and the occult; the supposedly open-minded, spiritual and romantic but in fact empty and vapid pursuits, the world is not without wonder and the numinous.

Love is what provides magic in the mundane world and brings colour to a

colourless palette. More to be felt than be defined, love nevertheless lured

many great artists to try. Emily Dickinson summed it up with ‘Love is all we

need and that’s all we need to know of love’, sometimes ineffectually shortened

to ‘all we need is love’. Yeats wrote in his drinking song, ‘Wine comes in at

the mouth/ And love comes in at the eyes;/ That’s all we shall know for

truth/Before we grow old and dies’. Both writers confirming the ineffability of

the great motivator. Perhaps Oscar Wilde sums it up best by observing that ‘The

very essence of romance is uncertainty’.

Comments

Post a Comment