The Myth of Sisyphus

|

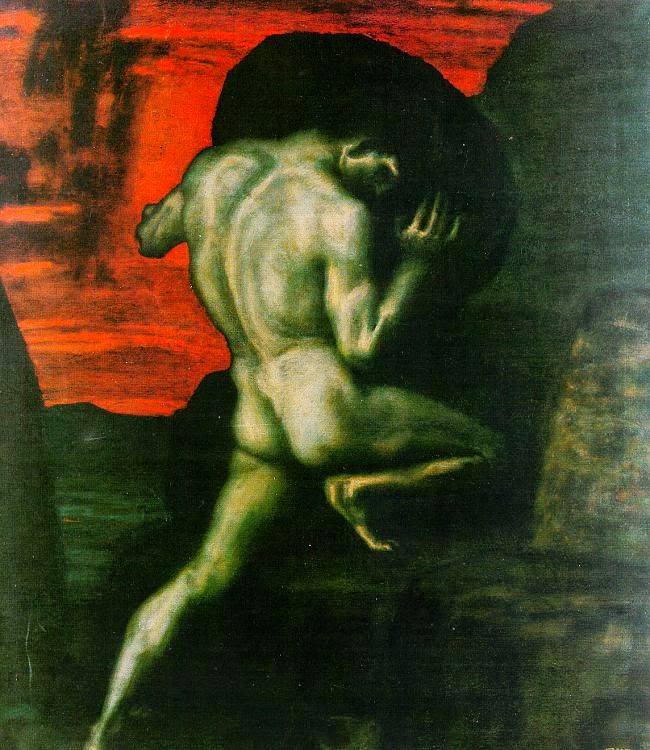

| Sisyphus by Franz von Stuck |

The great American writer

Mark Twain once remarked ‘The world owes you nothing; it was here first’. This

witty remark was made to combat the notion that one’s mere existence makes us entitled. A silly concept but one whose allure

everyone surely has at times felt. It is bred into the human species for each

individual to be solipsistic and egotistic for these traits carry with them

selective advantages. The ember of this stamp of our lowly origins is roused by

the cult of over exaggerated individualism, where everyone is led to believe he

or she is special and unique; two very ambivalent adjectives at best if one

pauses to think.

However, the ideology that best exploits this inbuilt weakness in the human nature is religion, or specifically the eschatological aspect of religions – where humans who subscribe to certain dogmas are said not only to be favoured and loved, but are also promised transcendence over that ultimate shared reality – death. Hence religion’s eternal appeal; as Freud pointed out in his The Future of An Illusion, religion will exist so long as men fear death. As the (as far as we know) only species on Earth who foresees that death is the final destination, to seek ways to escape it, a chance to transcend death is only natural and is indeed the carrot dangled on a stick of virtually all religions. So eager are we to be an exception to the subject of expiration that we grasp at any straw, no matter how frivolous or lacking in evidence, in the hope that death might pass us by.

However, there are those who have rejected the false consolation of religion and have chosen to accept death as the inevitable and inescapable endpoint of life. “I shall rot” was the terse answer of the philosopher Bertrand Russell when asked what he thinks will happen to him after death. Granted this, how then to deal with this sobering and melancholy burden of expecting the inevitable in the seemingly aimless flux that is life is the object of Camus’s Myth of Sisyphus. His antidote? – embrace the absurd.

However, the ideology that best exploits this inbuilt weakness in the human nature is religion, or specifically the eschatological aspect of religions – where humans who subscribe to certain dogmas are said not only to be favoured and loved, but are also promised transcendence over that ultimate shared reality – death. Hence religion’s eternal appeal; as Freud pointed out in his The Future of An Illusion, religion will exist so long as men fear death. As the (as far as we know) only species on Earth who foresees that death is the final destination, to seek ways to escape it, a chance to transcend death is only natural and is indeed the carrot dangled on a stick of virtually all religions. So eager are we to be an exception to the subject of expiration that we grasp at any straw, no matter how frivolous or lacking in evidence, in the hope that death might pass us by.

However, there are those who have rejected the false consolation of religion and have chosen to accept death as the inevitable and inescapable endpoint of life. “I shall rot” was the terse answer of the philosopher Bertrand Russell when asked what he thinks will happen to him after death. Granted this, how then to deal with this sobering and melancholy burden of expecting the inevitable in the seemingly aimless flux that is life is the object of Camus’s Myth of Sisyphus. His antidote? – embrace the absurd.

Life and death is the

ultimate duality. At the moment of birth one is hurtling towards death. It is

the fate all men and women, saint or scoundrel have or will have shared. Or as

Horace more eloquently put it ‘Pale

Death with impartial tread beats at the poor man's cottage door and at the

palaces of kings’. It is therefore the

great subject of philosophy and art. Philip Larkin, perhaps the least

sentimental of poets, captured beautifully in his Aubade the poignancy of honest

contemplation of death:

The sure

extinction that we travel to

And shall

be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be

anywhere,

And soon;

nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a

special way of being afraid

No trick

dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast

moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to

pretend we never die,

And

specious stuff that says No rational being

Can

fear a thing it will not feel, not

seeing

That this

is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch

or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to

love or link with,

The

anaesthetic from which none come round.

In it he dispelled the noble

but rather unattainable notion encapsulated by that great philosopher

Epicurus’s defiant declaration: ‘non fui, fui, non sum, non curo’ (I was not, I

was, I am not, I care not). It is something of a non sequitur to say one does

not fear the time before one’s birth. But to have existed, to have acquired the

ability to contemplate and extrapolate ourselves into the future and stare into

the abyss of death, that cavernous, mysterious, menacing darkness, and to do so

with equanimity is asking something that’s seemingly impossible.

For one who is convinced that death is the ultimate end, the question

then is: what is the point of life? Camus begins his dissertation with the

piquant statement ‘There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and

that is suicide.’ If life is only a

brief spark, possibly and probably filled with grief, melancholy, sorrow and

despair, devoid of meaning and rudderless, only to be followed by demise; can

you blame someone, upon realising this, to adopt the escape

route to arrive prematurely at the inevitable comfort of the eternal sleep? As

about a million people die of suicide each year, self-slaughter has been a

subject of intense interest in psychology and literature. The vacillation

between life and death is perhaps best captured by Shakespeare in Hamlet’s

famous soliloquy.

To be, or not to be,

that is the question—

Whether 'tis Nobler in the mind to suffer

The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die, to sleep—

No more; and by a sleep, to say we end

The Heart-ache, and the thousand Natural shocks

That Flesh is heir to? 'Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep,

To sleep, perchance to Dream; Aye, there's the rub,

For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause.

Whether 'tis Nobler in the mind to suffer

The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die, to sleep—

No more; and by a sleep, to say we end

The Heart-ache, and the thousand Natural shocks

That Flesh is heir to? 'Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep,

To sleep, perchance to Dream; Aye, there's the rub,

For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause.

Caught between the vice of a meaningless and absurd existence and the

terror of death and unable to take the leap of faith and succumb to the easy but baselessness of religion (an escape offered by Kierkegaard but which Camus calls

‘philosophical suicide’), how does one find meaning in life? Camus’s resolution

– accept the absurd and live in revolt against it.

Camus writes that with the realisation and acceptance of the fact that life is devoid of absolutes and meaning, what we achieve then is absolute freedom. Our very existence will then be an act of rebellion. Unshackled, we are able to think for ourselves and make our own meanings. While the search for an underlying meaning or purpose may be a doomed expedition, the struggle, the journey itself and the fruits we gain should be rewarding enough.

Hence Sisyphus, the king of Ephyra, cursed by the gods for his deceitfulness to forever push a large boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down, and compelled to repeat this fruitless labour for eternity. As a somber metaphor of life, we are all Sisyphus. Camus ends his book by concluding: ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy’. A flinty and stoic sentiment tinged with the wry smile of irony. This idea somewhat foreshadowed by the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, who wrote that ‘Death smiles at us all, all a man can do is smile back’.

Camus writes that with the realisation and acceptance of the fact that life is devoid of absolutes and meaning, what we achieve then is absolute freedom. Our very existence will then be an act of rebellion. Unshackled, we are able to think for ourselves and make our own meanings. While the search for an underlying meaning or purpose may be a doomed expedition, the struggle, the journey itself and the fruits we gain should be rewarding enough.

Hence Sisyphus, the king of Ephyra, cursed by the gods for his deceitfulness to forever push a large boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down, and compelled to repeat this fruitless labour for eternity. As a somber metaphor of life, we are all Sisyphus. Camus ends his book by concluding: ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy’. A flinty and stoic sentiment tinged with the wry smile of irony. This idea somewhat foreshadowed by the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, who wrote that ‘Death smiles at us all, all a man can do is smile back’.

A rather uninviting and rocky road, you might think; not a path strewn with

flowers. Well, not necessarily. Some bulwarks against the blues are irony and

humour. As the great novelist Kingsley Amis wrote, on the silver lining of this heavy subject:

Death has this much to be said for it,

You don’t have to get out of bed for it.

Where ever you happen to be,

They bring it to you – free.

You don’t have to get out of bed for it.

Where ever you happen to be,

They bring it to you – free.

Or as Monty Python offered in their immortal song Always Look on the Bright

Side of Life:

For life is quite

absurd

And death's the final word

You must always face the curtain with a bow

Forget about your sin

Give the audience a grin

Enjoy it, it's your last chance anyhow

And death's the final word

You must always face the curtain with a bow

Forget about your sin

Give the audience a grin

Enjoy it, it's your last chance anyhow

To appreciate irony can not only turn the sour grapes of life into wine

but will help you see things without illusions, without solipsism and to

realise that a life that partakes in only some of the myriad of worthy things

on offer in the smorgasbord of existence: love, friendship, parenthood,

literature and humour, cannot be called meaningless.

The journalist and essayist Christopher Hitchens, debating a fatuous and

overbearing William Dembski whilst suffering stage four cancer which eventually

took his life, summed up his life’s philosophy and his appreciation for the

absurd beautifully:

“…when Socrates was sentenced to death for his

philosophical investigations, and for blasphemy for challenging the gods of the

city — and he accepted his death — he did say, well, if we are lucky, perhaps

I’ll be able to hold conversation with other great thinkers and philosophers

and doubters too. In other words the discussion about what is good, what is

beautiful, what is noble, what is pure, and what is true could always go on.

Why is that important, why would I like to do that? Because that’s the only conversation worth having. And whether it goes on or not after I die, I don’t know. But I do know that that’s the conversation I want to have while I’m still alive. Which means that to me, the offer of certainty, the offer of complete security, the offer of an impermeable faith that can’t give way, is an offer of something not worth having. I want to live my life taking the risk all the time that I don’t know anything like enough yet; that I haven’t understood enough; that I can’t know enough; that I’m always hungrily operating on the margins of a potentially great harvest of future knowledge and wisdom. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

And I’d urge you to look at those people who tell you, at your age, that you’re dead till you believe as they do — what a terrible thing to be telling to children! And that you can only live by accepting an absolute authority — don’t think of that as a gift. Think of it as a poisoned chalice. Push it aside however tempting it is. Take the risk of thinking for yourself. Much more happiness, truth, beauty, and wisdom will come to you that way.”

Why is that important, why would I like to do that? Because that’s the only conversation worth having. And whether it goes on or not after I die, I don’t know. But I do know that that’s the conversation I want to have while I’m still alive. Which means that to me, the offer of certainty, the offer of complete security, the offer of an impermeable faith that can’t give way, is an offer of something not worth having. I want to live my life taking the risk all the time that I don’t know anything like enough yet; that I haven’t understood enough; that I can’t know enough; that I’m always hungrily operating on the margins of a potentially great harvest of future knowledge and wisdom. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

And I’d urge you to look at those people who tell you, at your age, that you’re dead till you believe as they do — what a terrible thing to be telling to children! And that you can only live by accepting an absolute authority — don’t think of that as a gift. Think of it as a poisoned chalice. Push it aside however tempting it is. Take the risk of thinking for yourself. Much more happiness, truth, beauty, and wisdom will come to you that way.”

Comments

Post a Comment